How Stress Affects Your Gut Health

At Daiwa Health Development, we recognize that modern life often brings relentless pressures, and understanding how stress affects gut health is crucial for maintaining overall well-being. Our commitment to functional medicine and high-quality supplements stems from years of research into the intricate connections between mental health, physical health, and the digestive system. Chronic stress can disrupt the delicate balance within your body, leading to issues that extend far beyond temporary discomfort, and we provide targeted solutions to support resilience against these effects.

Understanding Stress and Its Biological Impact

Stress represents a natural response to challenges, whether from external demands like work deadlines or internal factors such as emotional turmoil. It triggers a cascade of physiological changes aimed at preserving homeostasis, but when prolonged, it exerts a profound influence on various systems, including the gut. Psychological stress, in particular, activates the central nervous system, releasing stress hormones like cortisol that prepare the body for fight-or-flight scenarios. However, these same hormones can alter gut motility, slowing digestion or causing spasms that contribute to discomfort.

Multiple studies highlight that stress affects not only immediate responses but also long-term health outcomes. For instance, accumulating evidence from research in brain behav immun shows that persistent exposure to stressors correlates with heightened inflammation, which directly impacts the digestive tract. This connection underscores why managing stress levels is vital for preventing escalation into more severe conditions.

The Role of the Gut Microbiome in Health

The gut microbiome consists of trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, yeasts, viruses, and fungi, residing primarily in the intestines. These gut microbes play a pivotal role in digestion, nutrient absorption, and immune function. A healthy gut microbiome features a dominance of beneficial bacteria from phyla like Bacteroides and Firmicutes, which comprise over 90% of the bacterial population in humans.

Maintaining a healthy gut involves fostering an environment where advantageous gut bacteria outnumber pathogenic bacteria. Disruptions in this balance, known as dysbiosis, can lead to compromised intestinal health, making the body more susceptible to infections and inflammatory responses. The gut flora's diversity is essential for producing short-chain fatty acids that nourish the gut lining and support the immune system.

Defining the Gut-Brain Axis

The gut-brain axis serves as a bidirectional communication pathway linking the enteric nervous system in the digestive tract with the central nervous system. This gut-brain connection facilitates constant dialogue through neural, hormonal, and immune pathways, including the vagus nerve, which transmits signals between the brain and gut. Sensory neurons in the gut relay information about nutrient status and microbial activity, influencing mood and behavior.

Brain-gut interactions are particularly sensitive to stress, where elevated cortisol levels can impair this axis, leading to mood disorders and depressive symptoms. The vagus nerve's involvement means that stress-induced signals from the brain can rapidly affect gut function, while gut microbiota alterations can feedback to influence mental health.

Direct Ways Stress Influences Gut Physiology

Stress directly modifies gut physiology by increasing intestinal permeability, often resulting in a condition called leaky gut. This greater intestinal permeability allows harmful substances to escape the gut barrier into the bloodstream, triggering immune responses from cells like mast cells and immune cells. Such leaks compromise the intestinal mucosal barrier, fostering an environment where inflammation thrives.

Furthermore, stress affects gut motility, potentially causing constipation or diarrhea by disrupting normal peristalsis. In severe cases, this condition contributes to functional gastrointestinal disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease. Irritable bowel syndrome IBS, for example, often flares during periods of high perceived stress, illustrating the direct effect of psychological stress on the gut.

Changes in Gut Microbiota Due to Stress

Chronic stress reshapes the gut microbiota, promoting an overgrowth of inflammation-causing bacteria while diminishing beneficial bacteria. Studies in brain behav immun demonstrate that individuals under constant stress exhibit reduced diversity in their gut microbiome, tilting the balance toward dysbiosis. This shift in gut bacteria can exacerbate digestive disorders and weaken the gut's protective functions.

The molecular mechanisms involve stress hormones interacting with gut microbes, altering their metabolism and virulence. Preclinical findings suggest that these changes not only affect local gut health but also systemic well-being, as altered gut flora can influence neurotransmitter production, impacting mental health.

Increased Gut Permeability and Its Consequences

One significant impact of stress is the breakdown of the gut barrier, leading to increased intestinal permeability. This condition allows toxins and undigested food particles to enter circulation, provoking immune reactions that can manifest as allergies or autoimmune issues. Mast cells, activated by stress, release histamines that further widen these gaps in the intestinal lining.

In the context of inflammatory bowel disease, this permeability heightens the risk of flares, where the body's immune system attacks the digestive tract. Managing stress through targeted interventions can help reinforce this barrier, reducing the likelihood of such complications.

Alterations in Intestinal Function and Disease Risk

Stress induces changes in the functional physiology of the intestines, potentially leading to ulcers or conditions like Crohn's disease, a form of inflammatory bowel disease. Research indicates that early-life stress can predispose individuals to these issues later, showing the lasting imprint on gut health. Irritable bowel syndrome, another common outcome, involves spasms and pain linked to disrupted gut-brain signaling.

Moreover, stress heightens the risk of acid reflux by relaxing the lower esophageal sphincter, allowing stomach acids to irritate the esophagus. These alterations underscore the need for stress management to preserve intestinal health.

Indirect Effects Through Diet and Appetite

Stress indirectly harms gut health by influencing eating behaviors. It activates brain regions like the ventral tegmental area and amygdala via NMDA glutamate receptors, often leading to cravings for highly processed foods high in saturated fats. Continuous consumption of such processed foods disrupts the gut microbiome, favoring pathogenic bacteria over beneficial ones.

This dietary shift can result in an upset stomach, bloating, or irregular bowel movements, compounding the stress-gut cycle. Perceived stress often drives emotional eating, further straining the digestive system.

Metabolic Changes Induced by Stress

Beyond altering what we eat, stress modifies how the body metabolizes food. Individuals under stress show reduced fat oxidation, elevated insulin levels, and lower energy expenditure after fatty meals, as per studies in biol psychiatry. These metabolic responses can lead to weight gain and insulin resistance, indirectly affecting gut flora and increasing inflammation.

In a stressed state, the body's prioritization of immediate energy needs neglects long-term digestive efficiency, contributing to an unhealthy gut microbiome.

The Link to Broader Health Issues

Prolonged stress not only disrupts gut health but also elevates risks for psychiatric disorders, as imbalances in the gut-brain axis can worsen anxiety and depressive symptoms. The immune system's involvement means that chronic inflammation from a leaky gut may contribute to mood disorders.

Additionally, emerging links suggest that persistent gut dysbiosis under stress could increase susceptibility to colorectal cancer by promoting chronic inflammation in the digestive tract.

Strategies for Reducing Stress and Supporting Gut Health

Reducing stress is fundamental to restoring gut balance. Incorporating deep breathing exercises into your daily routine can activate the parasympathetic system, countering stress hormones and promoting relaxation. Regular physical activity, even moderate walks, releases endorphins that enhance mental health and stabilize gut motility.

A good night's sleep, aiming for seven to eight hours, allows the body to repair and rebalance the gut microbiota. These practices collectively lower cortisol levels, fostering a healthier gut environment.

Pro Tip: Integrate mindfulness techniques, such as meditation, to manage stress effectively; this approach not only calms the mind but also supports the gut-brain axis by reducing inflammatory signals.

Nourishing the Gut Through Diet

Adopting a balanced diet rich in whole grains, fibers, and fermented foods bolsters beneficial bacteria in the gut microbiome. The Mediterranean diet, emphasizing fruits, vegetables, and healthy fats, has shown promise in countering the negative effects of stress on gut flora. Avoiding highly processed foods and saturated fats prevents further disruption to gut bacteria.

Consuming adequate water throughout the day maintains the gut lining's integrity, helping to balance healthy and unhealthy microbes. Healthy foods like yogurt and kefir introduce probiotics that reinforce the gut barrier.

Exercise and Its Dual Benefits

Regular exercise serves as a powerful tool for stress management and gut health. It stimulates the release of anti-inflammatory compounds while enhancing gut motility, reducing the risk of constipation. Activities like yoga combine physical movement with deep breathing exercises, directly benefiting the gut-brain connection.

By lowering stress levels, exercise prevents the cascade of changes that lead to increased intestinal permeability and dysbiosis.

The Importance of Sleep for Recovery

Adequate sleep is non-negotiable for mitigating how stress affects gut health. During rest, the body regulates stress hormones and repairs the intestinal mucosal barrier. Chronic sleep deprivation exacerbates perceived stress, further imbalancing the gut microbiota.

Establishing a consistent sleep routine supports overall health, ensuring the digestive system functions optimally.

Incorporating Supplements for Enhanced Support

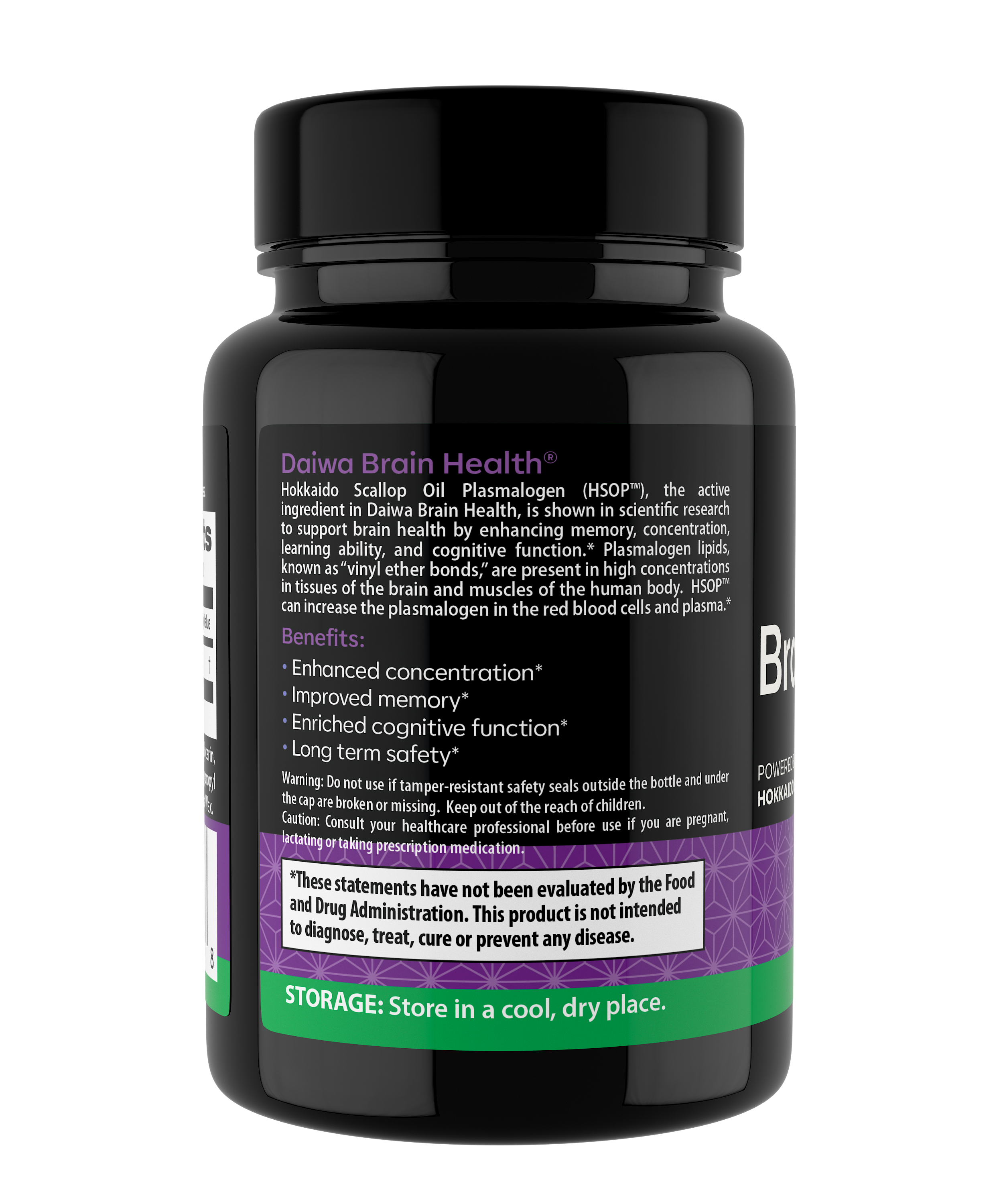

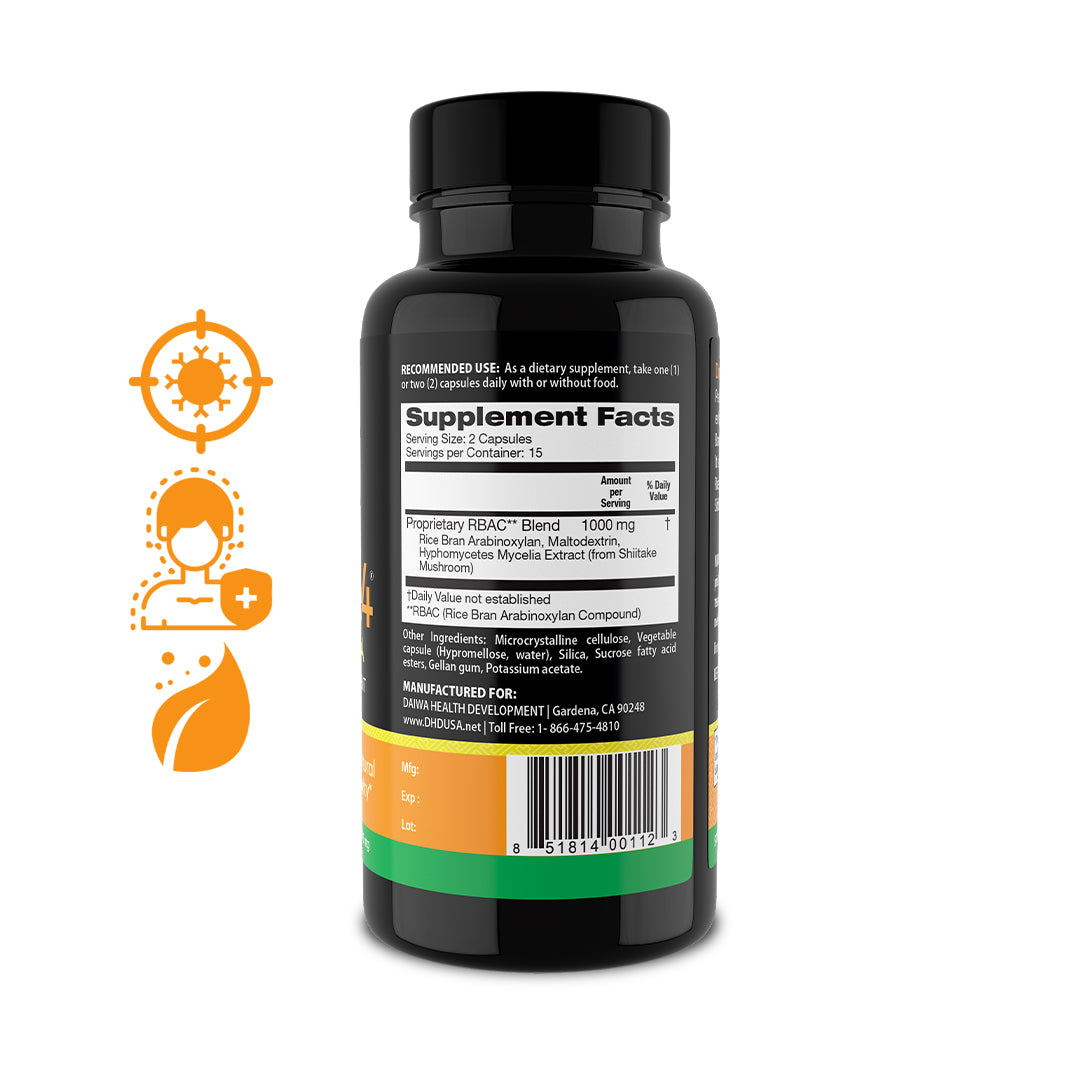

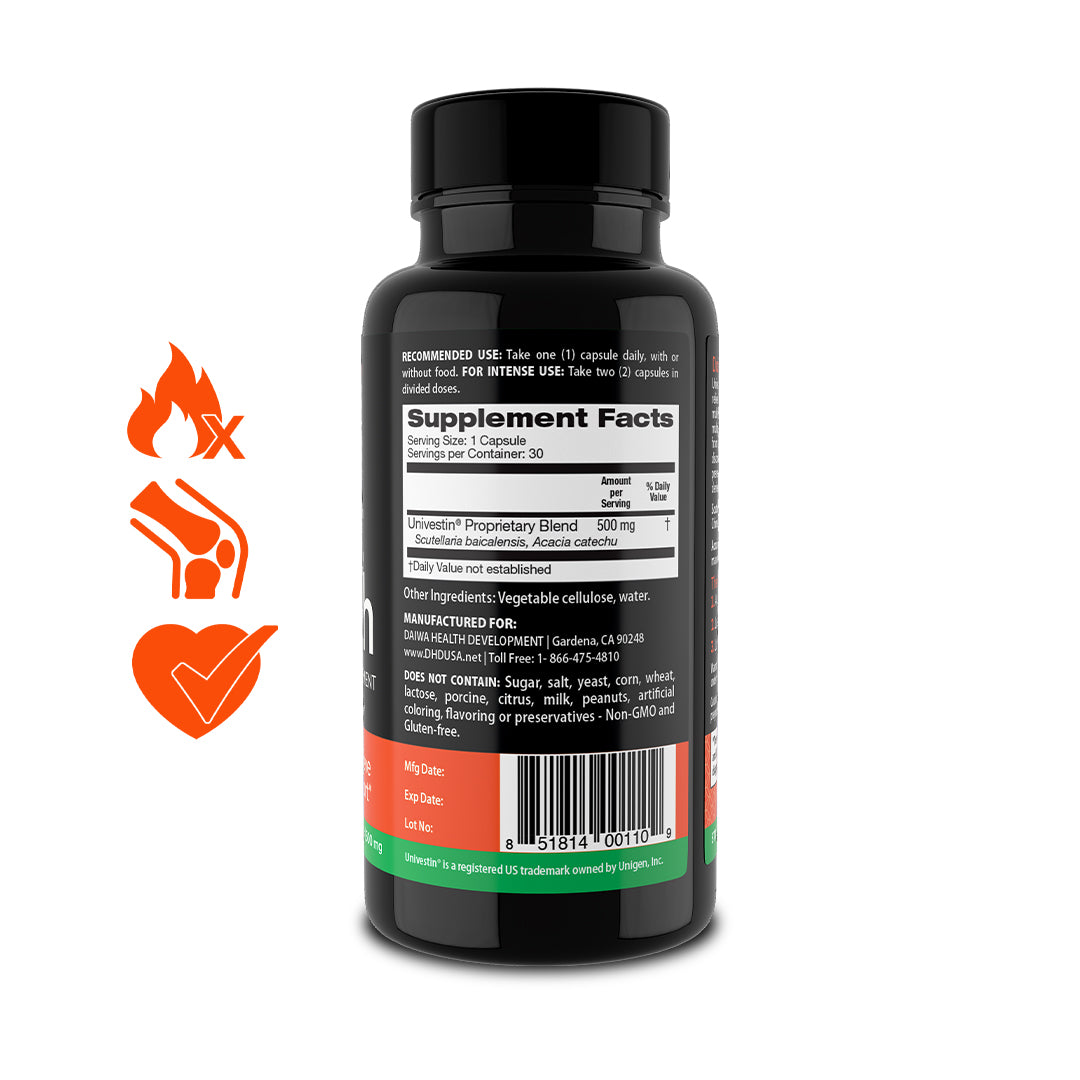

In the middle of navigating these challenges, Daiwa Health Development offers supplements designed to fortify the gut microbiome and to aid stress resilience. Our formulations, rooted in functional medicine, incorporate natural ingredients that promote beneficial bacteria and manage inflammation, helping to restore balance amid daily pressures. These products provide a practical way to enhance your efforts in managing stress and maintaining a healthy gut.

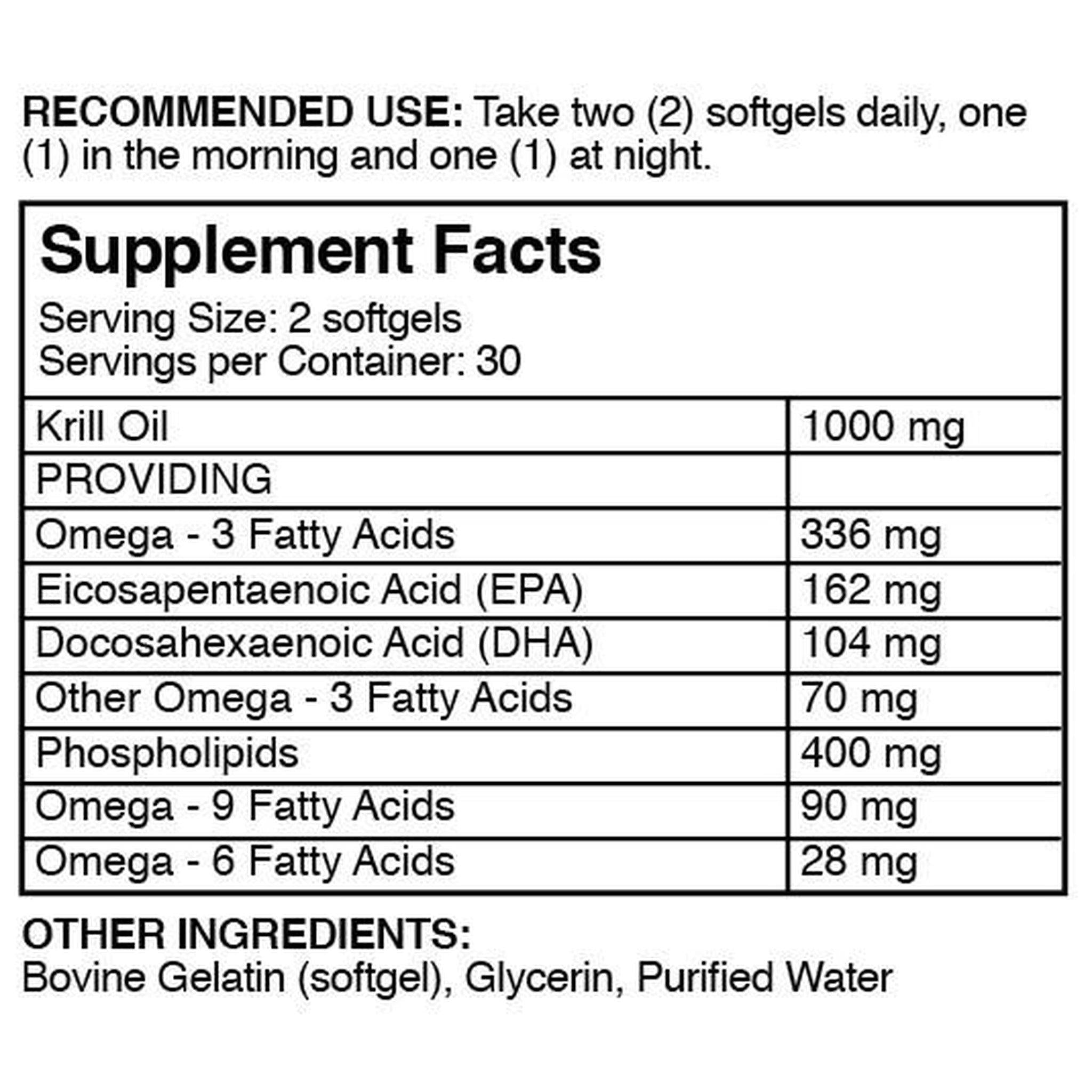

Healing the Gut from Chronic Stress

To heal your gut from chronic stress, focus on rebuilding the gut barrier through inflammation management trategies. Probiotics and prebiotics can repopulate beneficial bacteria, while omega-3s from supplements or diet manage inflammation. Reducing stress via therapy or lifestyle changes prevents further damage, allowing the gut to recover.

Consistent application of these methods reverses dysbiosis, improving mental health and physical health alike.

Resetting Gut Health Effectively

Resetting gut health involves a multi-faceted approach: eliminate triggers like processed foods, introduce a balanced diet, and prioritize stress management. Fasting intermittently can give the digestive tract a break, while incorporating fermented foods rebuilds gut flora.

Monitoring progress through symptoms like reduced bloating indicates success in achieving a healthy gut.

Pro Tip: Track your stress levels alongside dietary changes; this holistic view turns potential setbacks into opportunities for fine-tuning your routine, ensuring sustained well-being.

Long-Term Maintenance for Optimal Well-Being

Sustaining improvements requires ongoing commitment to reducing stress and nurturing the gut microbiome. Regular check-ins with healthcare professionals can identify early signs of imbalance, while a supportive community enhances mental health.

By addressing brain-gut interactions proactively, you safeguard against the recurrence of issues like irritable bowel syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease.

The Interplay with Immune Function

The gut houses a significant portion of the immune system, where stress-induced changes can weaken defenses. Mast cells and immune cells respond to stress hormones, potentially leading to overreactions that harm gut health. Strengthening this axis through lifestyle and supplements bolsters resilience.

Connections to Mental and Physical Health

The gut-brain axis links gut health directly to mental health, where dysbiosis can amplify anxiety. Physical health benefits from a stable gut, as it optimizes nutrient absorption essential for energy and recovery from stress.

Evidence from Systematic Reviews

A systematic review of studies in behav brain res confirms that stress significantly impacts gut microbiota composition, with interventions like probiotics showing reversal potential. This crucial role of targeted therapies highlights pathways for intervention.

Unique Insights from Functional Medicine

From our expertise at Daiwa Health Development, we observe that integrating adaptogenic herbs in supplements can modulate stress responses, protecting the gut-brain axis. This approach, combined with personalized nutrition, addresses root causes rather than symptoms, offering profound benefits for those facing chronic stress.

In conclusion, comprehending how stress affects gut health empowers you to take decisive action for better outcomes. At Daiwa Health Development, our supplements are crafted to support this journey, providing the tools needed to thrive. Embrace these strategies today to protect your well-being and experience the transformative power of a balanced body.

References:

-

Schneiderman N, Ironson G, Siegel SD. Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:607-628. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144141

-

Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016 Aug 19;14(8):e1002533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533. PMID: 27541692; PMCID: PMC4991899.

-

Roberfroid M, Gibson GR, Hoyles L, McCartney AL, Rastall R, Rowland I, Wolvers D, Watzl B, Szajewska H, Stahl B, Guarner F, Respondek F, Whelan K, Coxam V, Davicco MJ, Léotoing L, Wittrant Y, Delzenne NM, Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Meheust A. Prebiotic effects: metabolic and health benefits. Br J Nutr. 2010 Aug;104 Suppl 2:S1-63. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510003363. PMID: 20920376.

-

Jiang H, Ling Z, Zhang Y, Mao H, Ma Z, Yin Y, Wang W, Tang W, Tan Z, Shi J, Li L, Ruan B. Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2015 Aug;48:186-94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.03.016. Epub 2015 Apr 13. PMID: 25882912.

-

Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, Fagundes CP. Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry. 2015 Nov 1;172(11):1075-91. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15020152. Epub 2015 Sep 11. PMID: 26357876; PMCID: PMC6511978.

-

Hommes D, van den Blink B, Plasse T, Bartelsman J, Xu C, Macpherson B, Tytgat G, Peppelenbosch M, Van Deventer S. Inhibition of stress-activated MAP kinases induces clinical improvement in moderate to severe Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2002 Jan;122(1):7-14. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30770. PMID: 11781274.

-

Nasihatkon ZS, Khosravi M, Bourbour Z, Sahraei H, Ranjbaran M, Hassantash SM, Sahraei M, Baghlani K. Inhibitory effect of NMDA receptors in the ventral tegmental area on hormonal and eating behavior responses to stress in rats. Behav Neurol. 2014;2014:294149. doi: 10.1155/2014/294149. Epub 2014 Aug 7. PMID: 25177106; PMCID: PMC4143587.

-

Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Habash DL, Fagundes CP, Andridge R, Peng J, Malarkey WB, Belury MA. Daily stressors, past depression, and metabolic responses to high-fat meals: a novel path to obesity. Biol Psychiatry. 2015 Apr 1;77(7):653-60. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.05.018. Epub 2014 Jul 14. PMID: 25034950; PMCID: PMC4289126.